| resorc ( @ 2021-12-09 09:48:00 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Were There Dinosaurs on Noah’s Ark?

A visit to Kentucky's creationist museum, a conservative base in the culture war

searching for the elusive answer to a persistent question concerning the seeming gullibility of my fellow Americans—namely, why did 42 percent of adults surveyed this spring by Gallup say they believe that God created humans in their present form less than 10,000 years ago?—I recently found myself in the office of Ken Ham, the born-again Barnum behind Kentucky’s $35 million Creation Museum, debating a separate but related question, one whose existence I had not previously recognized but which became for me a source of instant paleontological delight: How could dinosaurs have coexisted with other animals within the teeming confines of Noah’s Ark? Because, you see, Noah’s Ark, in Ken Ham’s understanding of the world, was crammed stem to stern with dinosaurs. The cleverest creationists don’t deny the historicity of dinosaurs; they simply argue that they were alive at the start of the Flood, which, by their calculation, occurred approximately 4,350 years ago. (What happened to the dinosaurs after the waters receded is another story.) One sign of Ham’s genius—and he is, at the very least, a marketing genius—is his ability to shape a conversation on his terms, which is why I heard myself arguing against the possibility of a dinosaur-laden ark, rather than arguing against the notion that the ark itself was an actual thing that existed. My argument, in case you were wondering, is that the Tyrannosauruses would have eaten the sheep. QED, right? Except, no. “Many dinosaurs,” Ham says, “were smaller than chickens.”

But let’s not get ahead of ourselves. In the beginning, God created the heavens and the Earth. A short while later, Ken Ham found 40 acres of pastureland in northern Kentucky on which to build a museum devoted to the ideology of “Young Earth” creationism, which holds that the world is 6,000 years old, and which represents for a subset of evangelical Christians not only the most convincing explanation for how our planet, and the humans who rule it in God’s name, came into being, but also a potent weapon in the struggle against homosexuality and other modern ailments. What I didn’t understand until I visited Ken Ham is that his museum, which is devoted to a literal, historical reading of the first book of the Bible, is in itself a forward operating base in the conservative war against legalized abortion, gay marriage, and the belief that man is at least partially responsible for climate change (the creationists’ retort being that God will not allow man to destroy a world that he created).

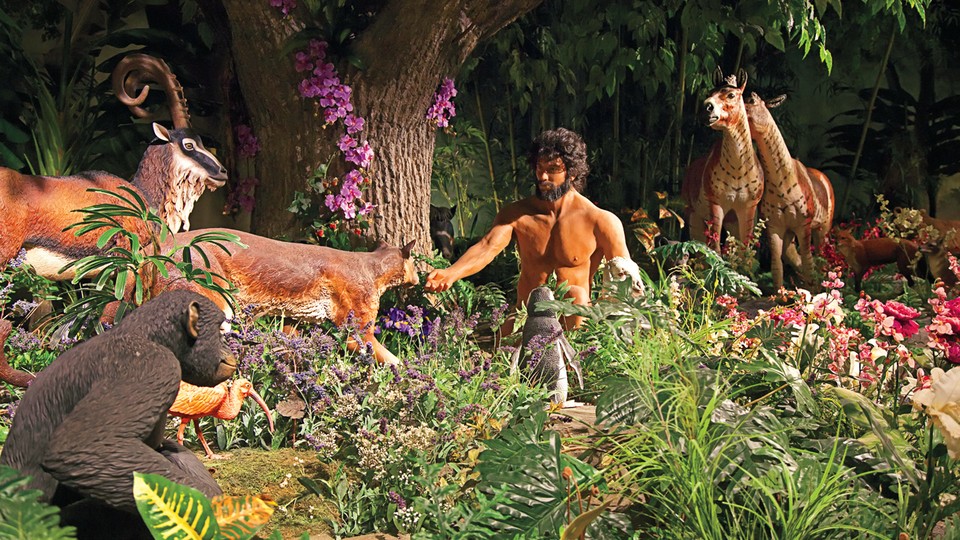

Ham is Australian—a rare sort of Australian, in that he is religiously devout and completely humorless—but he possesses a specifically American talent, one on display in mega-churches and theme parks across the country, for staging emotion-saturated high-tech spectacles. And so his museum is filled with buff animatronic Adams and sexpot Eves (plastic breasts covered by waterfalls of extremely healthy hair) and writhing snakes and flying dragons and dinosaurs much larger than the average chicken. The museum’s core argument is posted near the main entrance: “The Bible is authoritative, without error, and inspired by God.” Its other message to the Christian tourist market is left unstated: the Book of Genesis, in addition to being the source of holiness and cosmic truth, is also a source of Epcot-quality fun.

“Why shouldn’t we as Christians use the best technology we can?” Ham asked me, though I had not questioned Christians’ right to deploy Disney-level engineering in their museums. Ham is not only a creationist but an oppositionist. He knows that his ministry, Answers in Genesis, draws the scorn of sophisticates, and so he takes special delight in portraying himself as a rational Daniel in the lions’ den of militant secularism, the lions being the media and the scientific establishment and the ghost of Clarence Darrow and millions of liberal and even not so liberal Christians and pretty much anyone who disagrees with Ken Ham.

My sympathies, by the way, do not lie entirely where you might think. I find atheism dismaying, for Updikean reasons (“Where was the ingenuity, the ambiguity … of saying that the universe just happened to happen and that when we’re dead we’re dead?”), and because, in the words of a former chief rabbi of Great Britain, Jonathan Sacks, it is religion, not science, that “answers three questions that every reflective person must ask. Who am I? Why am I here? How then shall I live?” Like Ken Ham, I am appalled by the idea, as expressed by Richard Dawkins, that “the universe we observe has precisely the properties we should expect if there is, at bottom, no design, no purpose, no evil, and no good, nothing but blind, pitiless indifference.”

Luckily, I belong to a tradition that, in addition to creating the Bible (one of Ham’s colleagues was nonplussed to learn that I could recite passages of Genesis in the mother tongue), came to understand, per Maimonides, that the first chapters of Genesis contain stories meant to advance an understanding of universal, ethical monotheism, rather than scientific explanations for creation. A faith that demands uncompromising fealty to a literal reading of its origin story seems to me a perilously brittle faith.

Many of the Creation Museum’s exhibits are devoted to refuting the body of scientific knowledge accumulated over the past two centuries concerning the formation and development of our planet and its living beings. A full-size animatronic Noah, speaking English in a Count Chocula accent, answers questions about dinosaur husbandry. A placard alongside a mounted dinosaur bone poses a Smithsonian-worthy challenge: “Can you tell how old this fossil is? Fossils don’t come with tags on them that tell us how old they are. We have to study the clues we find to try to figure out their ages.” But then the next placards tell us that the answers are found exclusively in the Bible. “The Bible says God created everything in 6 days. He created people and land animals on Day 6,” and “Adam was the first man. He was created on Day 6. By adding up the ages of Adam, his sons, their sons, and so on, we see that the Earth is about 6,000 years old.”

The final sign reads: “A flood explains why we find billions of dead things, buried in rock layers, laid down by water, all over the Earth. Can you think of an event in the Bible where tons and tons of water flooded the whole Earth?” I toured the museum trailing a family of five from Ohio. The mother read the question to her three sons. They answered correctly. “Why did God send a flood?” The oldest boy answered: “To kill the wicked people.” She then asked: “Will he do it again?” No one answered. “God only punishes the unsaved,” she said. It was at this point that I should have introduced myself.

Instead I followed them to another exhibit, this one quite unlike those devoted to dinosaur apologetics. This exhibit presents with blunt force the case against godlessness, depicting the lives of modern families that have made the tragic error of rejecting the literal truth of God’s word. “In this 7 minute video,” one introductory placard reads, “the boy in the background is ‘on a killing spree’ on his video game. His older brother is looking at internet pornography and has a bag of drugs.” The mother said, “You have to listen to your parents.”

The Creation Museum is not a museum so much as it is a 3-D hellfire sermon with a food court.

Sitting with Ken Ham and Terry Mortenson, a historian of geology and a theologian on staff, I asked why it is so important to convince their visitors—more than 2 million since the museum opened seven years ago—that Genesis is a book of history. “There’s a slippery slope in regard to authority,” Ham replied. “If you say that the history in Genesis is not true, then you can just take man’s ideas as true. When you go outside of Scripture, why shouldn’t you just reinterpret what marriage means? So our emphasis is on the slippery slope regarding authority.”

Did he ever wake up in the morning and have doubts about the truth of the Bible?, I wondered. “No,” he said. “Show me another book in the world that claims to be the word of one who knows everything, who has always been there, that tells us the origin of time, matter, space, the origin of the Earth, the origin of water, the origin of the sun, moon, and stars, the origin of dry land, the origin of plants, the origin of animals, the origin of marriage, of death and sin,” he said.

“Lord of the Rings?,” I answered, tepidly.

“Well, there’s no book so specific as the Bible,” he said.

Mortenson stayed on the subject of gay marriage. “The homosexual issue flows from this. Genesis says that God created marriage between one man and one woman. He didn’t create it between two men, or two women, or two men and one woman, or three men and one woman, or two women and one man, or three women and one man. If other parts of Genesis aren’t true, then how could this idea of marriage be true? If there were no Adam and Eve and we’re all evolved from apelike ancestors and there’s homosexuality in the animal world and if Genesis is mythology, then you can justify any behavior you want.” I found this preoccupation with gay marriage significant, because it suggests that perhaps at least some of those who profess a belief in creationism might simply be signaling their preference for a more traditional social order, rather than a rejection of modern science and free intellectual inquiry.

As I said goodbye, the co-founder of the museum, Mark Looy, brought me a shopping bag filled with books making the case for Young Earth creationism. “Happy early Hanukkah,” he said. As I left the museum, I saw the same family I had been trailing in the exhibit. I introduced myself to the mother. “What did you think of the museum?,” I asked. “It explains everything,” she said.