| I’ve written mine with the idea that books are not useful at all. |

[Jan. 13th, 2018|04:42 pm] |

intelektuālā māja bedre.

vjetnamieši pa šo gadu ir paguvuši izdot vēl vienu Fukuokas grāmatiņu.

Some years ago, Fritjof Capra, a professor of theoretical physics at the University of California who also lectures on science as a holistic discipline, visited my hillside hut. He was troubled that the current theories of subatomic particles appeared to be incomplete. There ought to be some fundamental principle, Capra said, and he wanted to express it mathematically.

In searching for this elusive fundamental principle, he had found a hint in the Taoist concept of yin and yang. He called it the science of the Tao, but he added that this alone did not solve the puzzle.

He had likened the lively dance of subatomic particles to the dance of the Indian god Shiva, but it was difficult to know what the steps of the dance were, or the melody of the flute. I had learned about the concept of subatomic particles from him, so of course I had no words that could directly dispel his frustration.

It is one thing to think that within the constant changes of all things and phenomena there must be some corresponding fixed laws, but humans cannot seem to be satisfied until they have expressed these laws mathematically. I believe there is a limit to our ability to know nature with human knowledge. When I mentioned this might be the source of his problem, Capra countered, saying, “I’ve written more than ten books, but haven’t you written books, too, thinking knowledge was useful?”

“It’s true that I have written several books,” I responded, “but you seem to have written your books believing they would be useful to other people. I’ve written mine with the idea that books are not useful at all. It appears that both of us, from the West and the East, are investigating nature and yearning for a return to nature, so we are able to sit together and have a meeting of the minds. But on the point of affirming or negating human knowledge, we seem to be moving in opposite directions, so we probably will not arrive at the same place in the end.”

In the end, it will require some courage and perhaps a leap of faith for people to abandon what they think they know.

Scientists have historically assumed that it is acceptable to control nature using human will. Nature is seen as the “outside world” in opposition to humanity, and this idea forms the basis of modern scientific civilization. But this fictitious “I” of Descartes can never fully comprehend the true state of reality.

Just as human beings do not know themselves, they cannot know the other. Human beings may be the children of “Mother Nature,” but they are no longer able to see the true form of their mother. Looking for the whole, they only see the parts. Seeing their mother’s breast, they mistake it for the mother herself. If someone does not know his mother, he is a child who does not know whose child he is. He is like a monkey, raised in a zoo by humans, who is convinced that the zookeeper is his mother.

Similarly, the discriminating and analytical knowledge of scientists may be useful for taking nature apart and looking at its parts, but it is of no use for grasping the reality of pure nature. One day scientists will realize how limiting and misguided it is to hack nature to pieces like that.

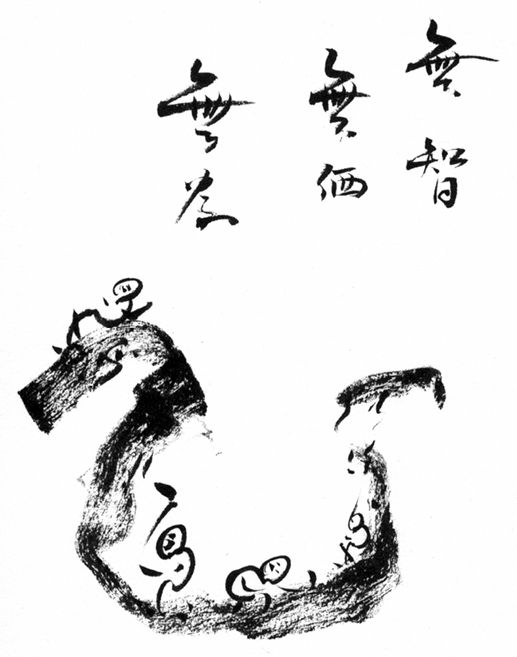

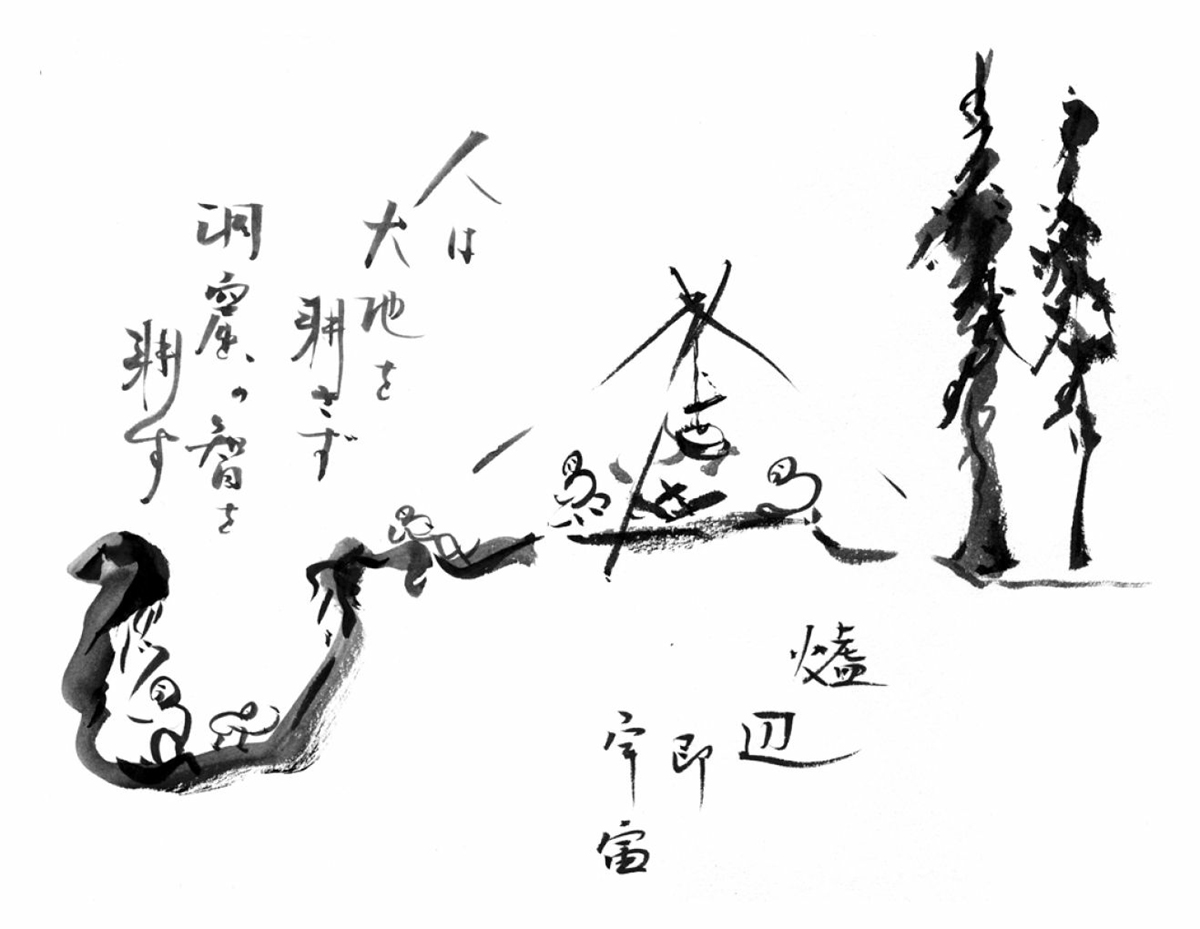

I sometimes make a brush-and-ink drawing to illustrate this point. I call it “the cave of the intellect.” It shows two men toiling in a pit or a cave swinging their pickaxes to loosen the hard earth. The picks represent the human intellect. The more these workers swing their tools, the deeper the pit gets and the more difficult it is for them to escape. Outside the cave, I draw a person who is relaxing in the sunlight. While still working to provide everyday necessities through natural farming, that person is free from the drudgery of trying to understand nature, and is simply enjoying life.

Masanobu Fukuoka, „Sowing Seeds in the Desert”

ņemts no tejienes |

|

|